The American Center for Craft, Creativity and Design posts some background on Theosophist Reginald Machell not used in the book Makers: A History of American Studio Craft by Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf published by the University of North Carolina Press, July 2010. Machell, who was born in England in 1854, died at Point Loma, California, in 1927. He met Blavatsky in London and did some of the designs at the Theosophical Hall that was opened in 1890 at the Headquarters at 19 Avenue Road. In 1900 he moved to Point Loma, California, where he arrived on December 28. “At Point Loma, he carved chairs, screens and stools decorated with forms reminiscent of Art Nouveau, Celtic interlace, Gothic tracery, flames and wings. They are wonderfully inventive, completely unlike any other furniture made in America.”

The post, which can be read here, explains: Theosophy was created in 1875 by a charismatic Russian occultist named Helena Blavatsky (1831-1891), who melded elements of Hinduism, Buddhism and sheer invention into a quasi-religion that drew numerous followers around the turn of the century. Blavatsky held that anyone could attain a higher level of consciousness, and that this spiritual work was a matter of direct experience, not requiring the mediation of any church. Theosophy attracted people troubled by the materialism of the age and hungry for a more personal experience of the spiritual.

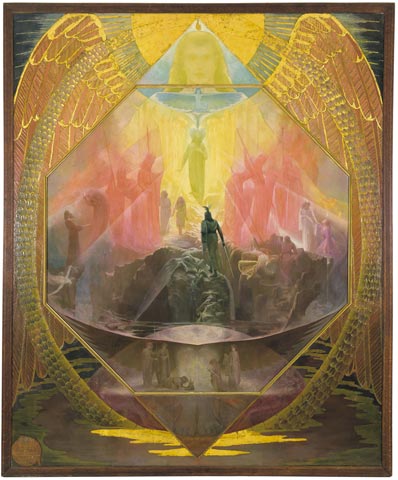

Machell is best remembered for his painting, “The Path” (6’2” x 7’5”), which is housed at the headquarters of the Theosophical Society, in Pasadena, California. The frame, made by him, is another example of his ornate woodwork. Reginald Machell’s output as part of the Theosophical experience is documented in Bruce Kamerling’s essay, “Theosophy and Symbolist Art: the Point Loma Art School” in The Journal of San Diego History, Volume 26, Number 4, Fall 1980, which can be seen here.